sections

intro

I take forever to write. The steps all use different muscles so sitting down during the weekend and trying to do all of them is frustrating. It’s like cooking soup while also growing the herbs from scratch.

So I write across multiple sittings, jotting down rough ideas. Do this often enough and you’ll stumble into something usable. When I’m stuck though, I like having a toolkit of approaches to try instead of shooting blindly.

Here’s one approach:

Every little building block of a song adds context and value to the other blocks.

Which calls for two kinds of writing— coming up with blocks, then fitting them together. This post goes over the first kind! I’ll use one of my songs, no, f!!ck all that, as a case study.

what are blocks

In this framework1, we split songs into blocks. A block can be a line of lyrics, a phrase, or even a chorus. A block is our unit of analysis for songcraft.

Now, reframing songs this way is only be helpful if it gives us new information. So what we can learn from splitting the lyrics to no, f!!ck all that into blocks?

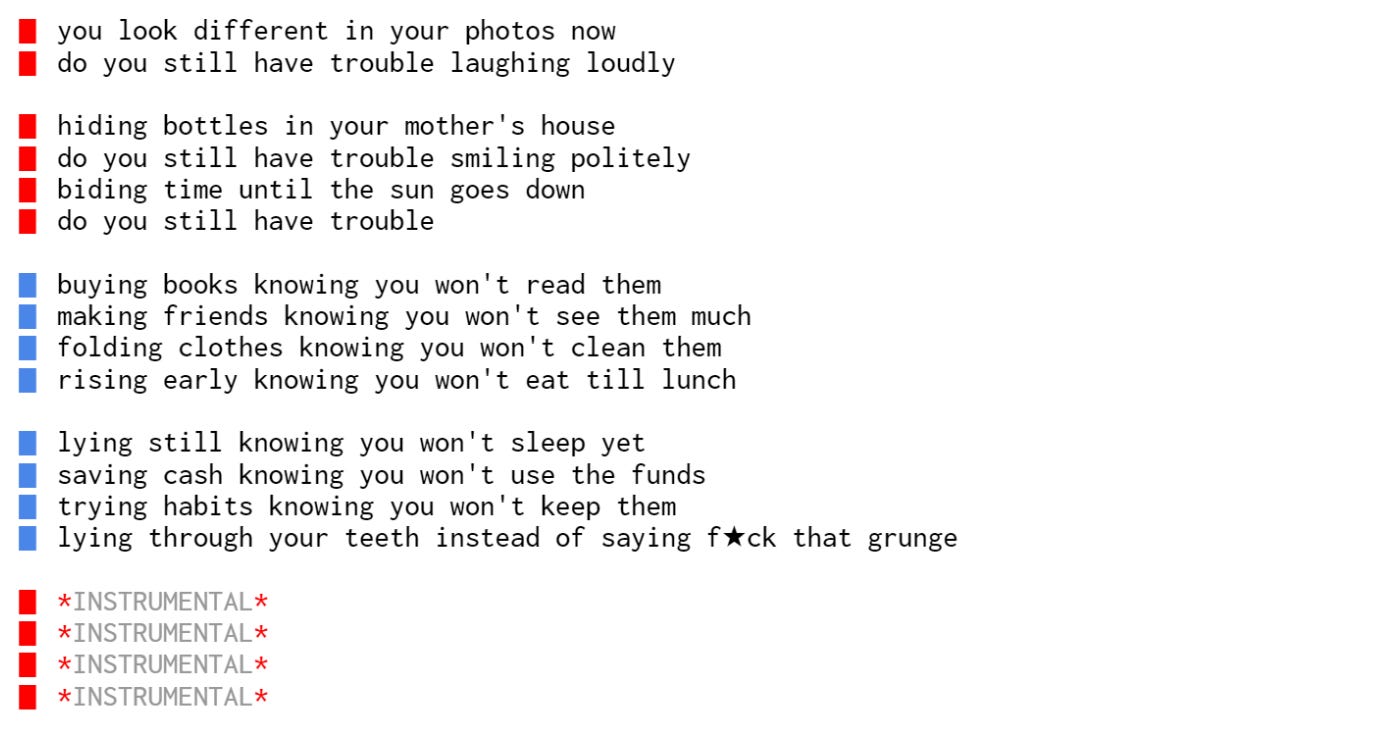

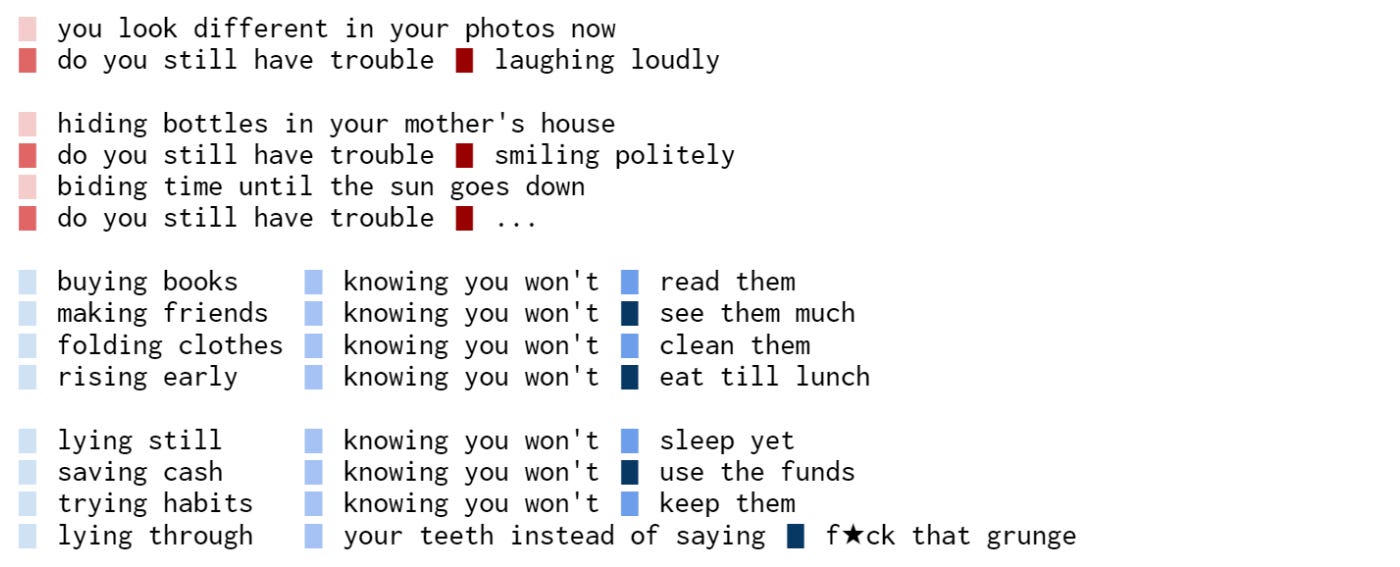

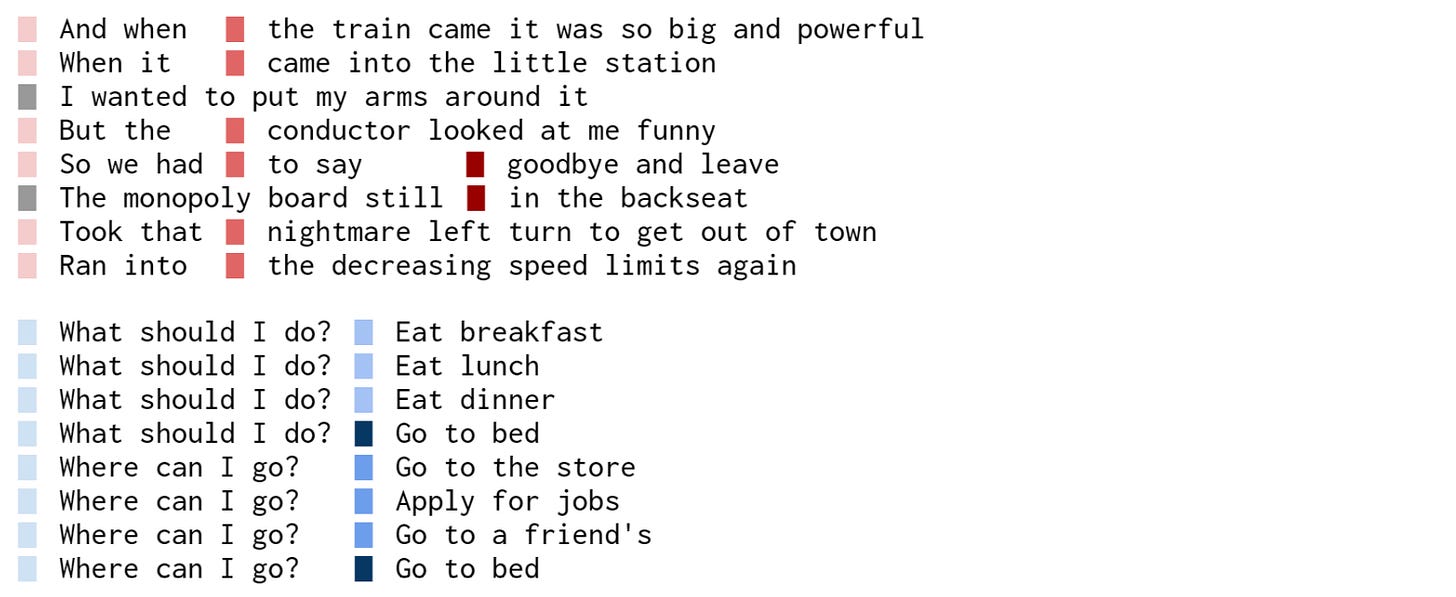

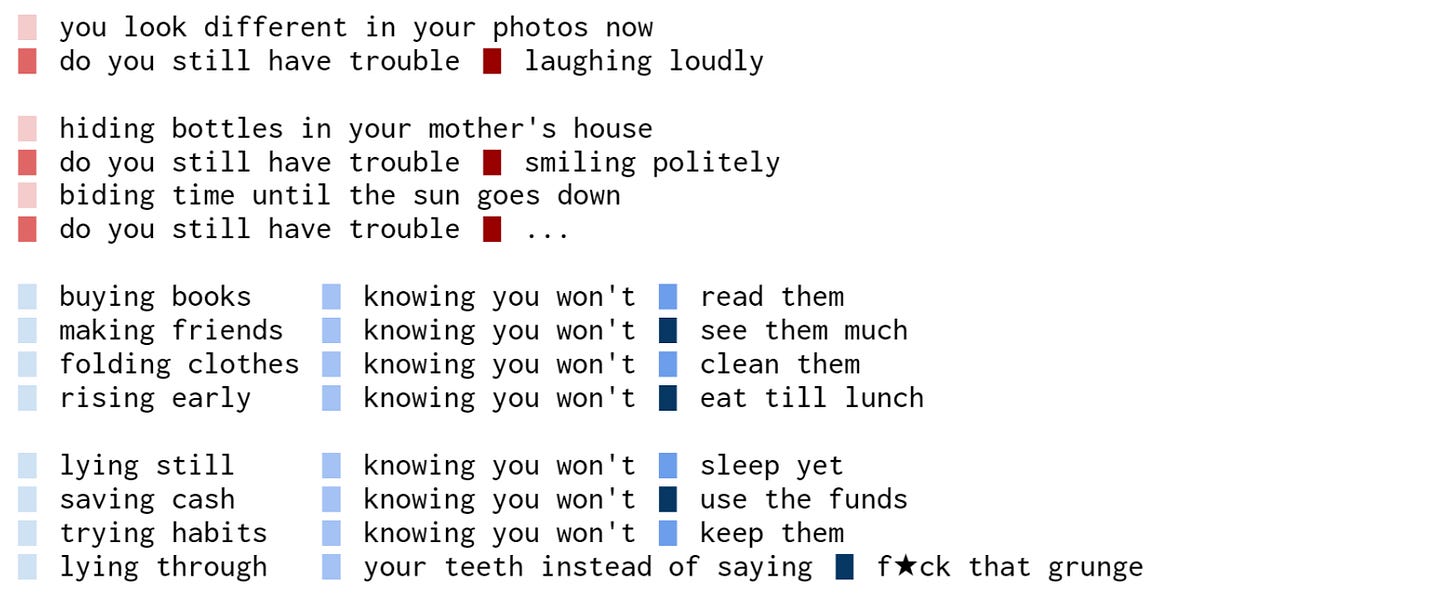

The song’s made up of SECTION BLOCKS— a red chorus block, a blue verse block, and an instrumental repeat of the red chorus block. Each section has two sub-sections, and those sub-blocks are made of individual LINE-BLOCKS.

We can split the LINE-BLOCKS down into PHRASE-BLOCKS.

RED-1 blocks are full lines,

RED-2 blocks are “do you still have trouble”,

RED-3 blocks are [conflicted actions],

BLU-1 blocks are [healthy actions],

BLU-2 blocks are “knowing you won’t”,

BLU-3 blocks are two-syllable [follow-up actions],

BLU-4 blocks are three-syllable [follow-up actions]Now we can zoom out and see the song as more than noises happening over time. There’s some patterns and maybe an internal logic.

what are structures

A group of blocks is a structure (a larger block with a fancy name), and we can see multiple structures in the lyrics!

SECTION-ST of CHORUS + VERSE + CHORUS-INSTRUMENTAL

CHORUS-ST of [RED1] + [RED2 + RED3]

VERSE-ST of [BLU1 + BLU2 + BLU3] + [BLU1 + BLU2 + BLU4]These structures2 are helpful, because we know their roles in different genres. In American pop,

a CHORUS-STRUCTURE is catchy,

a VERSE-STRUCTURE has most of the story,

and a BRIDGE-STRUCTURE appears before the last CHORUS-STRUCTURE.

We’ve just described a SECTION-STRUCTURE with roles for each SECTION-BLOCK. But we’re less aware of the structures we make as we fill in those verses and choruses. We hum and write them out of habit. So once we identify a structure, we can guess at how it works and modify it. We can write new material while building on our song’s internal logic.

types of roles

Since songs do a lot, blocks play many roles. We might find a:

STORY-ROLE, how does it build story?

PACING-ROLE, how does it affect momentum or pacing?

AESTHETIC-ROLE, how does it feel or sound satisfying?

MOTIF-ROLE, how does it introduce and repeat ideas?

Let’s revisit the lyrics.

Viewed through their STORY-ROLE,

INTRO-ST sets up the narrator and audience as old friends.

CHORUS-ST is a [coping mechanism] then an [ongoing issue]

VERSE-ST is a [attempt to get better] then a [struggle to follow-up]Viewed through their PACING-ROLE,

INTRO-ST has [long-winded melody] over [stabby organ] and [no drums]

CHORUS-ST has [long-winded melody] over [messy fast drums]

VERSE-ST has [shorter phrases] over [stabby organ] and [clear half-time drums]Viewed through their MOTIF-ROLE,

INTRO-ST introduces the [question format]

CHORUS-ST repeats with more questions.

VERSE-ST introduces a new format with a longer question.The lines also have a structure of call-and-response3, or question-and-answer. One sets up a call, then the next line responds and resolves it.

But these structures and their roles didn’t exist from the beginning! I had the first two lines, thought they were cool, and tried to repeat them. I came up with examples for the STORY-ROLES and then adjusted the words to fit the PACING-ROLE.

Bolding stressed syllables and copy-pasting on a writing program helps with maintaining the structure. It also shows if a rhythm is clunky, so I don’t need to rewrite the whole line, just the clunky bits left over. I then use the highlighter to mark different blocks.

a process

So the process looks like:

Stumble into a compelling line/verse/idea

Break it down

Where are the SECTION-BLOCKS?

What are the smaller structures?

What ideas, rhythms, and rhymes are repeated?

What roles might these blocks play in the final song?

Copy the structures and modify them (..v004b..)

Shuffle new blocks around in the structures

It helps me figure out why an idea works and then cut additions that don’t work as well. It separates writing a story from crafting its delivery. If we were filmmakers, it would be the difference between writing scripts and shot lists.

I recommend trying this on one section of a song you wrote, and then one section of a song that you dearly love. Bonus points if one inspired the other. no, f!!ck all that is inspired by Beach Life-in-Death, so there’s a structure comparison in the Appendix.

outro

This isn’t exactly a tutorial. Those imply final products.

I do like having a final product, but my goal isn’t to finish songs or tell others how to. Writing is a joy. I like the satisfaction of cutting syllables to make rhythms work, the nostalgia of grafting lyrics onto new albums, balancing what I want to say with what has good rhymes, and feeling clever and special and crafty. I like the feeling of watering my garden!

Too often, online advice assumes our goal as artists is hit-making and monetization. Even if it was good advice (and it’s usually not) it’s a terrible framing of what to expect. There’s a whole industry for coaching and tutorials that feels misguided to me. Seeing writing as an ongoing practice instead of a production-pipeline makes more sense for most small artists. It avoids the crushing expectations we put on final products.

The work and motivation of industry artists is different from ours, so the process is too. And the process is something I think we can all fall in love with. Make the process healthier, and eventually good art finds its way to you. If I knew more theory I’d write about how we should resist commodifying our art, especially if it draws from our lives, because not everyone has a right to consume it— to consume us.

So my goal isn’t to pretend I have solutions to ~*optimize*~ your process for maximum traffic. In my experience, I do my worst work with that approach. It’s distracting at best and demoralizing at worst. Instead, I want to highlight why I love this thing and how parts of it are intrinsically rewarding. Like so much of my life, this post is just a clearance-aisle version of a point CJ The X exemplifies.

So, yeah! I hope this helps. Go write something!

appendix

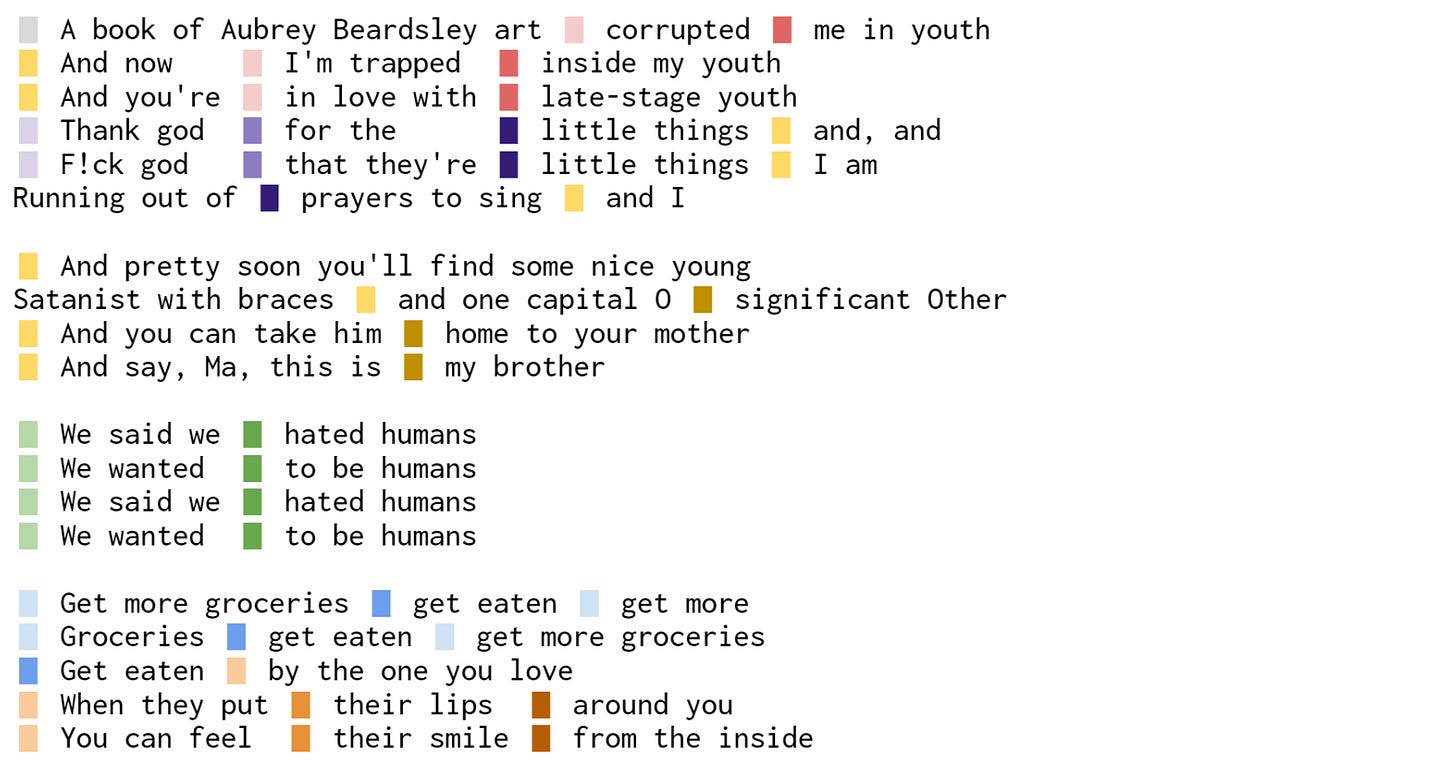

Songs usually cover a lot of story with minimal detail, so they’re comparable to montages in film. You need enough structure to connect the short scenes and enough detail to make them memorable. So I’m a big fan of Will Toledo’s constant switches between long-winded conversational lyrics and snappy, short phrases. The long lyrics feel like narration while the short phrases feel like insert shots. It’s a bit cinematic!

Here’s a snippet from Beach Life-in-Death..

And then from no, f!!ck all that..

This gets a lot more complicated later in the song (6:52)..

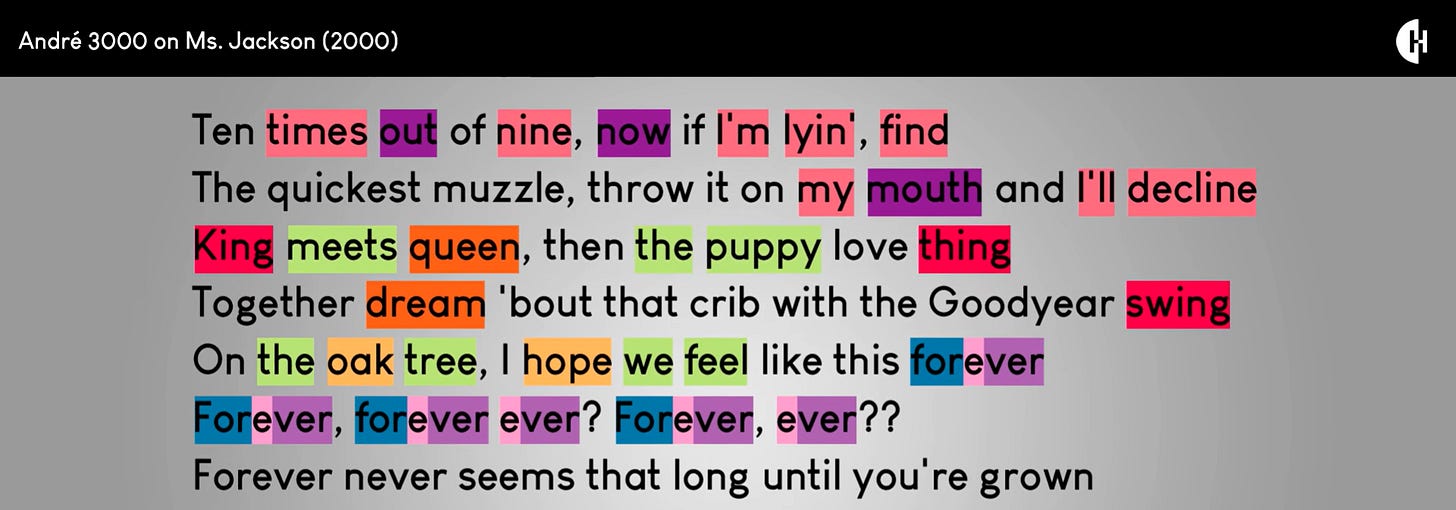

This is heavily inspired by a fantastic genre of videos highlighting rhymes and structure in rap music, see André 3000’s verse on Ms. Jackson for a great example!

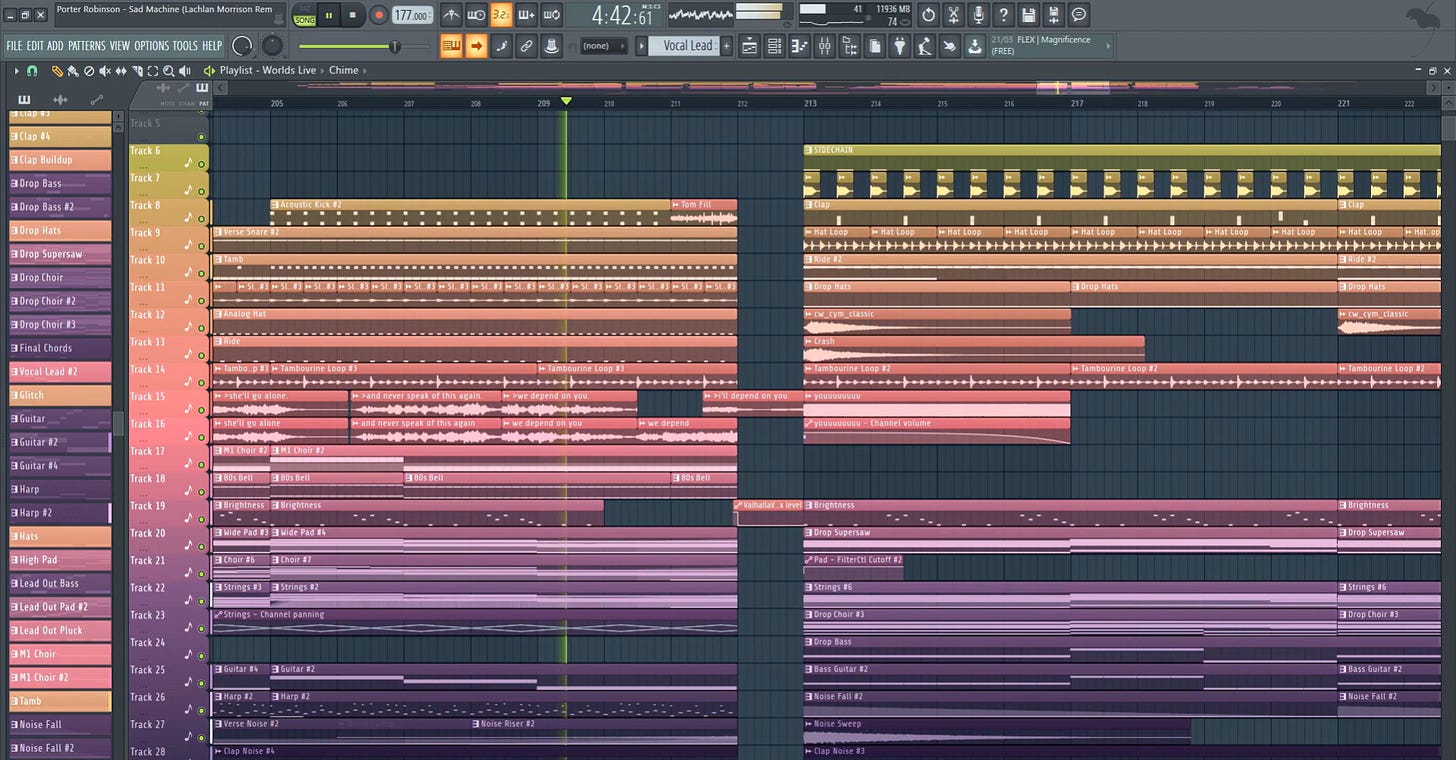

For visuals of larger song-structures, I love “FLP REMAKE” videos that show how the instrumentals interact with structure too. I learned a lot about songwriting from Lachlan Morrison’s eerily accurate remakes of Porter Robinson and Madeon songs.

In music theory, this is called antecedent-consequent-period. See a 1-minute video and a great blog post on it.