shinies - gaps (v007b)

(more) art about grief

CONTENT: Each of these pieces explores death and grief. I’ve included more detailed content warnings beside each piece (such as for suicidality, overdoses, and abuse), but they’re all heavy in their own way.

I think their power comes from exploring these topics with empathy, but they might not be the right media at the right time for you and that’s okay too. Take care of yourself, whether that includes interacting with these or not.

If you’re struggling, please consider resources like the National Institute of Mental Health, PLFAG’s LGBTQ+ hotlines, and Mental Health America. The search may be long but it will be worth it.

This is the follow-up to shinies - gaps (v007a).

Someone Great, LCD Soundsystem (TW: death of a loved one)

I AM NOT WHAT REMAINS, ompuco (TW: photosensitivity, narrator dying)

Videotape (2006 Bonnaroo Soundboard), Radiohead (TW: suicidality)

(★) EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE OKAY, alienmelon (TW: photosensitivity, surviving abuse, suicide, see artist statement)

Song for Dennis Brown, The Mountain Goats (TW: death, overdose)

(★) i will not survive you, bignastytruck (TW: death of a loved one, see artist statement)

True Love Waits (1995 Brussels Debut), Radiohead

NOTE: The first part of this was a lot easier to write. I had a through-line about the human need to grieve and the inhuman demand to return to normal as quickly as possible. The world’s not the same after death but your job probably will be. These last three pieces are more disparate.

EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE OKAY1 shows a chaotic recovery, a present distorted by the past’s lingering violence.

The structure is a bizarre computer desktop. Each program has a scene that plays like a WarioWare minigame from hell. Its visual layers are drawn with clashing resolutions and colors.

The characters’ pitched-up voices are pithy, gleeful, and grating, often slipping into cruelty while talking to the rabbit we play as. In one scene, we choose between three insultingly accommodating responses as talking worms downplay our implied abuse. They groan after we do and slink out of sight.

EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE OKAY flips our familiarity with user interfaces and human conversations into hostility. These systems should make sense, we know they did at one point, but they’re alienating and incomprehensible now, at the very moment where we need them the most.

Here, healing is made as absurd as the violence that made it necessary. EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE OKAY unflinchingly depicts how the conditions people grieve in (and our expectations of them) can be deeply unfair.

From Nathalie Lawhead’s2 artist’s statement—

“We don't really have a concept, in our culture, or discussion about alternative views of power from a survivor's standpoint. How is it like for survivors? Are people that live with trauma strong? Are people with mental disorders, or PTSD strong...

...We don't popularly view survivors, victims, traumas, etc, as strength. It is a weakness, and I don't like that. I think this is because we have created a culture where we cannot really ever move past pain. We don't teach people how to heal, to overcome, or be powerful. We teach people to be perpetual survivors.

We live with pain, but no way of transcending it...

...Surviving is one thing, but living with it is an entirely different fight, and I think this is where examples of real strength are.

If approached from this point of view then it is an obvious conclusion that you should be celebrated simply for being here. You are normal for your imperfections, and the way you cope. You are the hero in the story of your life, and you have every right to be proud.”

I don’t think I’ll finish EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE OKAY for a very long time. Beneath its irony-drenched pixels, EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE OKAY is furious. It gives us room to be too.

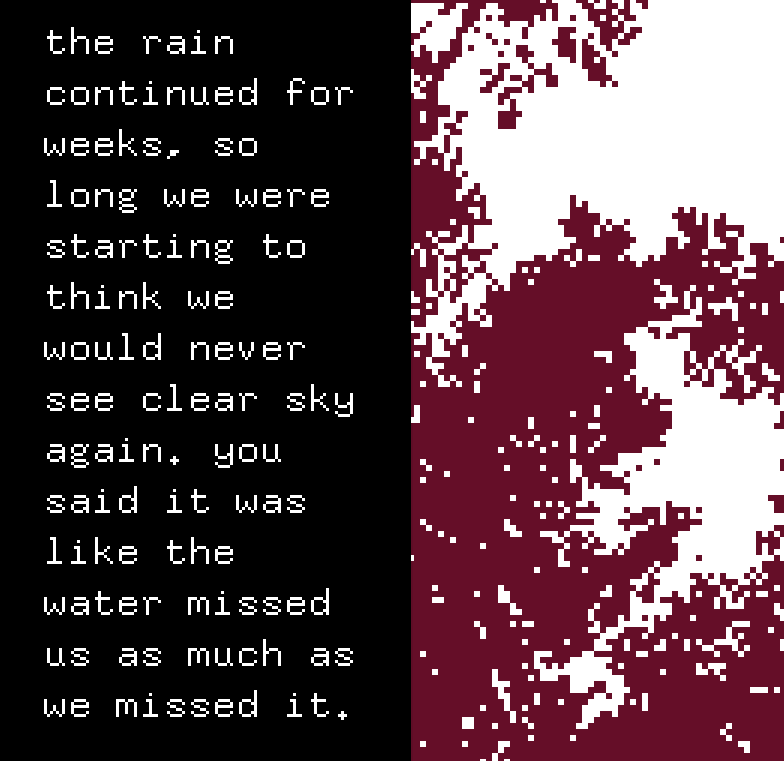

On the opposite end of presentation and tone, i will not survive you is haunting. It’s only minutes long, so play it blind if you can.

The framing is simple — a narrator talks to someone, let’s call them the beloved, on the screen’s left half. On the right are pixelated videos of tree leaves and mud. Sounds of wind, water, birds, and a soft acoustic guitar loop.

The narrator talks about floods tearing through the ground and seeding mulberry trees after weeks of rain. Bad luck, new life. The birds love the trees and fight with squirrels for their berries.

Intimate scenes between the narrator and beloved revolve around their strange new orchard. They bake a mulberry pie, come home with juice-stained lips, pluck berries from hair, patch up an overeager climber. I like how each scene has its own bit of bad luck — superstitious partygoers avoid the pie, juice stains the sheets. The beloved reacts kindly every time.

Something in it clicked for me when I realized the beloved had passed away. In-game, we listen as someone remembers us. In reality, we’re watching someone talk to a headstone.

Later, the narrator mentions we were buried last month, “out back with the mulberry trees”. We don’t see why. Probably bad luck. Can they tend to it as kindly as the beloved did, with a chuckle and patient hands? Can new life follow? The narrator cares in their own way, crafting chairs to spend afternoons in together and a headstone amid the trees.

The understated randomness behind the beloved’s offscreen passing matches the understated randomness behind all the ways they’re remembered. Why would these moments, of all the moments in a lifetime together, come to mind? Why would they happen at all?

The trees are something natural that we try to pull blame and meaning from but they’re too omnipresent to explain just the good or the bad. If they’re to blame for some of it they’re to thank for everything else too.

So they don’t really settle the question. i will not survive you almost gives us an answer—

I said once, bitterly, on a bad day near the end, that maybe you were right: maybe the trees were bad luck.

You smiled that smile again, the one that said you kind of liked the idea, and you held my hand.

You said, “if a long life spent here with you was the result of bad luck, then I’m happy to have had it.”

True Love Waits (1995) is a love letter to someone who’s not with us anymore, unboxed from our collective online attic3. The official 2016 release came twenty years later as the last song on Radiohead’s last album.

True Love Waits (1995) is a young man with a guitar. True Love Waits (2016) sees him singing softly over a mess of drifting, syncopated piano notes. It’s a soft, shifting echo of the original’s optimism and desperation.

And true love waits // In haunted attics // And true love lives // On lollipops and crisps // Just, don't leave // Don't leave

I'm not living // I'm just killing time // Your tiny hands // Your crazy kitten smile // Just, don't leave // Don't leave

It’s a song about utter devotion, about love giving someone purpose and their fear of losing it. Small intimate moments flash by as pieces of a relationship that we, the audience, don’t get to see fully, and maybe also as an imperfect memory that’s already leaving the narrator.

After the narrator admits to not really living, “tiny hands” and a “crazy kitten smile” pull him from the haze. The verses loop back to a seemingly simple ask — “Just, don’t leave, don’t leave”.

My favorite part is the synth arpeggio starting at 2:04, underscoring “And true love lives // On lollipops and crisps.” It’s so hopeful and tender, practically soaring above the guitar by the end4.

Even as the details slip, the song suggests our love lingers. It haunts spaces just outside of sight, it sticks to mundane objects we used to share. It fills the gap. I still think about how a much younger Thom Yorke introduces it — “This is a brand new song nobody’s heard before.”

I hope it’s one you love.

If you can’t run it, the developer posted this clip of the gameplay—

Nathalie Lawhead is behind projects that helped me fall in love with indie games. Her blog is delightful and her Electric Zine Maker undergirds many of my favorite itch.io zines.

I’m not sure how to discuss this responsibly or tastefully, but I’ll try. Thom Yorke had a relationship and two children with an artist named Rachel Owen, who died of cancer in 2016.

I don’t know Thom or Rachel, so I’ve tried to separate my own feelings about this from who I imagine them to be. Hopefully the background opens up an empathetic, rather than voyeuristic reading of the song.

Oddly enough, I started a relationship right before writing this blog’s first part that ended while I was working on this followup. True Love Waits, one of the earliest pieces I wanted to write about, bookends this post, my relationship, Radiohead’s monumental career, and maybe Thom and Rachel’s too.

I don’t like to literally match instruments to ideas (like they might in a soundtrack, where some horn introduces every scene with a character). But the synth here functions like the idea of love throughout, it surges up and re-contextualizes the song’s insecurity.

So of all the changes the 2016 release makes, I felt the synth’s absence most heavily. With it, True Love Waits (1995) crashes out into something wonderful and new. Without, True Love Waits (2016) fades out on a lone piano note.